DEPRIVATION RESEARCH

Gaining Insight into Behavior Change

What happens when you take away something deemed “essential”? And what happens when you replace that necessity with something

else entirely? Is the need being met, or are users deprived? Will behaviors change, will those changes be short term or long term? Will new opportunities or barriers reveal themselves? These are some of the questions that deprivation research seeks to answer. This creative method unearths raw, organic reactions to products and services and ultimately helps get teams beyond incremental innovation to explore future alternatives and what-ifs.

WHAT IS DEPRIVATION?

You’ve probably heard the term ‘deprivation’ before, but not in this way. Clues about why deprivation is a valuable learning mechanism permeate our pop culture: embedded in our diets, in religion, and within the lines of favorite musical ballads. When we decide (or are forced) to go without something, we often learn about ourselves in the process.

When we talk about deprivation as a design research methodology, we are talking behavioral prototype testing or interventions. Deprivation research studies force users own behaviors into relief – removing or altering aspects of their routines to better understand what drives their habitual behaviors in the first place, and how it may (or may not) change.

Let’s first acknowledge the methodological elephant in the room: the act of deprivation is often innately artificial – but this artificiality brings with it the ability to project ahead and leapfrog current market landscapes. When we cut the cord on TV access from users in the early 2000s, the experiment our participants endured was in fact artificially created. Who would do that?! But what it did allow was for us to organically simulate the migration to new behaviors that would go on to become mainstream years later: online content streaming. The insights that deprivation studies generate can often be ahead of their time, giving the teams who use them a competitive edge and a lasting knowledge base.

NEEDS VS. WANTS

The core definition of deprivation is “the lack or denial of something considered to be a necessity.” So it stands without saying that in order to conduct a deprivation study, you must first begin with a basic understanding of the needs and wants of your users.

What decides a need versus a want? As humans, we have a hard time distinguishing this difference. Many of the things we “need” may be wants in disguise that have become so deeply embedded in our routines that they feel like a need. Deprivation research isolates the tensions between needs and wants to identify the levers that truly make something essential. We use these studies to examine the specific material, social, emotional or physical benefits that are at play.

When routines are disrupted, favorites are taken away we are able to observe how people choose to cope (… or cheat) and what they do to compensate for what is lost. This modified behavior reveals the core needs, instinctual responses and motivations that might be difficult for users to fully articulate otherwise. By creating a little chaos this habit disruption creates new avenues for innovative thinking to surface.

Beyond just surfacing a refined articulation of needs, deprivation also fast tracks learnings to reveal the future barriers and limitations to behavior change and adoption. Where are users flexible, and where are they rigid? Do they invent new strategies or adapt their behavior to new use occasions? The answers to these questions provides new opportunities and guardrails for future product and service innovations.

HOW DEPRIVATION WORKS

Step 1

UNDERSTAND THE CURRENT HABIT LOOPS

Step 2

DESIGN INTERVENTIONS

Step 3

OBSERVE & UNDERSTAND

Step 4

IDENTIFY INSIGHTS

Establishing a baseline of existing behaviors and routines is a critical first step to deprivation – if you don’t take the time to get to know your participants natural behaviors and routines first, how can you design an appropriate intervention?

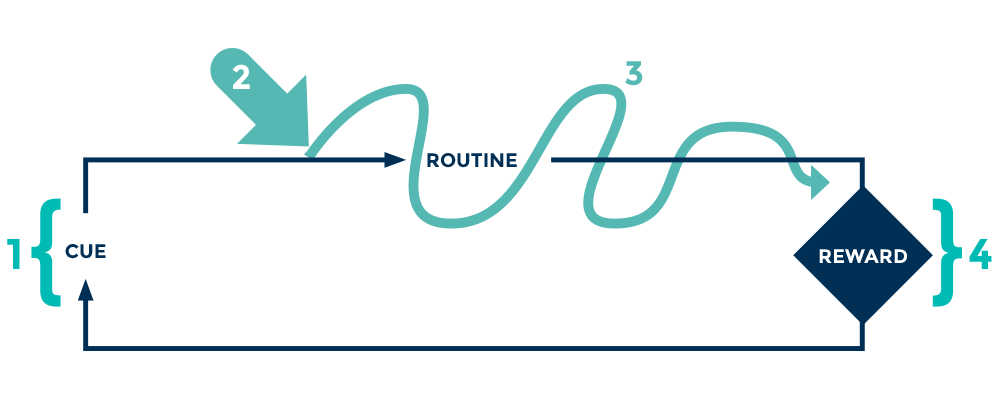

We use Charles Duhigg’s Habit Loop as our starting foundation for understanding how habits work. Understanding and deconstructing existing habits allows us to design interventions and alternative experiences that let us to assess the opportunities (and barriers) to behavior change.

Understanding & Disrupting the Habit Loop using Deprivation:

Step 1

Step 2

Step 3

Step 4

INSIGHTS AROUND

BEHAVIOR CHANGE

Isolate and understand experiences that are deeply embedded in routine

Better understand triggers, cues, routines and rewards

Understand levers and barriers to behavior change

Identify unmet needs and explore opportunities for creating new habit loops

MOMENTUM FOR

PRODUCT INNOVATION

Fast-track innovation, aiming to explore future states ahead of large shifts and trends

Test a product and record the adoption or rejection of alternatives

Identify how a prototype might replace existing offerings

Explore how different packaging forms or delivery might impact behavior and use

TYPES OF DEPRIVATION STUDIES

There are two main approaches to deprivation research –

Let’s break them down.

TAKE AWAY

This approach is exactly what it sounds like – the removal of a product or aspect of a participant’s routine. This literal act of deprivation allows us to explore the void and absence. How do users cope without something? Are there withdrawal symptoms? How quickly do they adapt and find workarounds on their own? Is their behavior permanently altered once habitual patterns are broken?

This type of deprivation invites participants to put their own routines and habits into relief and discover things about themselves. The result is a reflective and thoughtful foregrounding of important aspects of users routines that we wouldn’t necessarily normally get. Even when giving up an aspect of their routine is difficult, the process of documenting their deprivation experience provides opportunities for participants to recognize the discomfort, catharsis or humor involved in the experiment.

Read on for a case study about TV Deprivation & Migration to OTT.

REPLACE

The second approach to deprivation research involves both the removal and replacement of solutions – taking away their go-to solutions and swapping in an alternative solution. These alternatives may take many forms: futureoriented alternatives, similar substitutions, or even intentionally sub-par alternatives can be used as learning devices. Replacements are typically designed to match routines as closely as possible, while breaking or disrupting them through smaller nudges

Take for example behaviors around food & beverage consumption, media habits, communication methods, cleaning routines: many of these are so deeply ingrained that they become subconscious choices that users make every day. The replacement approach allows us to investigate the subtle and unspoken needs surrounding products that are “automatic”.

Our goal during replacement missions is to break the routine and expose new information about whether or not alternatives have permission to fulfill the original need. Ultimately this leads us to a richer understanding of the why behind deeply ingrained habits: Can new habits successfully be created? Are there opportunities for new cues and rewards to better support the routine? Are there unmet needs that emerge from the disruption of the routine?

Read more about a snack swap replacement study we did in partnership with Ferrara Candy Company.

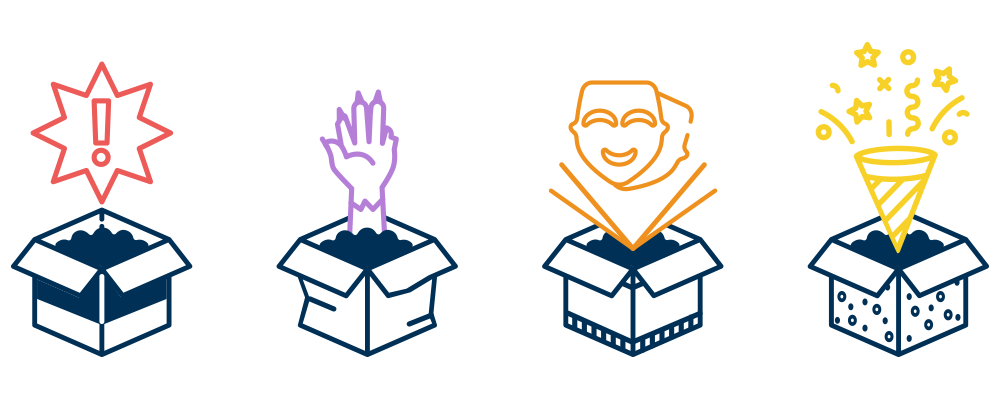

UNBOXING INSIGHTS

The moment of the reveal to participants during deprivation studies is one of the most critical moments of the study: how will users react to the mission they have been tasked with? Getting these unfiltered, instinctual, candid reactions on camera is a high-priority!

To get the most out of these reveals, we create “gifts” for our participants, packaging up any replacement items or creating a reveal experience for their deprivation mission that they will open and react to on camera.

Why a gift? In your usual focus group, products that participants react to are often just lab stimuli put forth on a table that become easily interrogated and critiqued. This yields “me vs. it” feedback that isn’t always productive for our research goals. When deprivation reveals are delivered as gifts with special care and presentation participants feel invested. That changes the script and invites a sense of curiosity and openness – ultimately yielding better data.

Gifts

Opens minds Invites investment and curiosity Feels special Sets a playful tone

vs.

Lab stimuli

Establishes a Me vs. It relationship Invites interrogation Context leads to projected use, not actual Impersonal and “not for me”

Read more about other ways that learning from Unboxing Moments can surface new insights.

CASE STUDIES

Cast your mind back in time to 10 years ago. Remember what it was like to watch your favorite shows. You certainly weren’t able to do it on your phones or laptops. Instead, you had to be seated in front of a television screen at the same time as the rest of the world.

We partnered with NBC, MediaVest, and Microsoft to conduct a study about migrating television viewing habits from linear television to internet streaming. This was in the pre-migratory period, when Netflix’s DVD Subscription was disrupting the media space and Hulu was just launching their beta platform. People didn’t have any well established mental models of how they would watch television programming anywhere else but their television sets.

We began with self-documentation activities and ethnographic immersions to establish a baseline of their viewing behaviors. After getting to know their routines, we asked them to take a journey with us as a household and then, quite literally, pulled the plug. No one in the household was allowed to watch television via cable or broadcast TV. The catch? They were free to find any alternative method of viewing their content, and they were encouraged to get creative. As our participants endured this period of deprivation, they documented their experiences as a household.

We also built in lifelines for a one-time-only cheat when they got desperate. During the deprivation period, participants could watch a single show live, so they had to choose wisely! The study took place right around season finales and what we found was that, more than anything else, the one thing that people could not give up was whatever “McDreamy” cliffhanger was going on in Grey’s Anatomy. This told us a lot about the moments when the stakes were too high to miss out on live content that was a social and cultural event.

Without cable or broadcast television at their disposal, people applied their existing mental models for searching the internet to the challenge of finding their desired shows. The workarounds they invented to access content online foregrounded the pain points and behavior changes that would emerge in the early days of migrating television online. This resulted in insights that covered searching for content, plug-ins, paywalls, subscription and access barriers, and expectations around when and where they would find both new and old content.

We also learned from what people didn’t do when they were deprived access to traditional television. At the time there was quite a healthy skepticism about whether people would accept the experience of watching on smaller screens such as phones or laptops. We found that users chose to adapt to smaller screens with little friction. They immediately traded convenience for screen size and if they were able to find something online, their computers were sufficient. The role of the TV set as the modern hearth around which families gather was changing.

The insights generated from this work remain relevant today as OTT migration continues to scale in the US. Many of the insights generated from this study remain challenges for media companies, as they perpetually work on improvements for meta-data algorithms, user experience, mobility, personalization and system-level constraints.

Innovation in the food space is a constant pursuit. Identifying the needs against which to innovate can be hugely challenging. Users’ preferences for certain snacks and candies can be difficult for them to articulate. These behaviors can be so routinized that people rarely reflect on them. Over the course of years, they have been influenced by personal tastes, food trends, nostalgia and childhood memories, social interactions, and simple distribution and availability.

Conifer partnered with Insights and Leadership teams across brands at Ferrara Candy Company for a foundational study to understand current consumption behavior and shopping journey for candy and snacks. This multi-phase program began with baseline immersive ethnography and culminated in an online Deprivation/Replacement study designed to identify the behavior change implications of different forms of product packaging. The objective of these learnings was to inform Ferrara’s packtype innovation pipeline.

Want to learn more? Check out our presentation from where we dive deeper into this study!

We gained insight into consumers existing behaviors and needs through diary activities, ethnographic immersions and shop-alongs. Along the way, participants began to express what they wanted from new products and packaging formats. We decided to put their desired solutions to the test in the deprivation study, giving some of them exactly what they asked for while giving others subpar substitutions that tested the extreme opposites of their preferences. Would people accept or reject the products we gave them? Would alternative packaging types and portions change the use cases?

As we tweaked and nudged people’s deeply entrenched routines, we got back highly emotional responses ranging from surprise and delight to annoyance and frustration. While getting these reactions was great fun, there was also a serious intent behind them. We were looking to test the real-world value of some long-held organizational beliefs about the preciousness of certain packaging differences. By carefully designing our deprivation to disrupt participants to respond and reflect on new snacking and candy realities, the Ferrara team was able to make concrete next steps on innovation in packaging, and even rethinking some of the capital being spent to provide infinite options at the shelf.

Did you like what you read? Fill out the form below for a downloadable version and take it with you!